Where's the offense in the NFL?

Pundits will tell you scoring is down in the NFL because of 'shell' coverage, but it's more nuanced than that.

We have a crisis two weeks into the NFL season: passing numbers are down.

Passing has been trending downward since 2021, but we are seeing a significant dip to start the 2024 season. The NFL is cyclical, but the numbers we are seeing this year are different, as Kevin Cole (Unexpected Points/former Data Scientist at PFF) pointed out about my viral tweet from this week (below).

From ‘20 to ‘22, NFL teams scored over 100 passing TDs to start the year. That number dipped to 86 last year and dipped even further (69) this season. We know the NFL has natural ebbs and flows, but we are seeing something historic. Full stop. No hyperbole. A clear trend is beginning to appear.

It’s not just TDs. Passing yardage is down as well. From 20-’22, NFL teams passed for an average of 263 yards in the season's first two weeks. In ‘23, that number dipped to 238. We currently sit at 216. Alarm bells are ringing.

Big Time Throws (a pass of high value and difficulty, i.e., deep throws) are substantially down as well and started to take a dip in ‘22. In ‘20 and ‘21, the NFL had well over 100 BTTs through two weeks. That number dropped to 70 in ‘22, raised back to 80 in ‘23 (whew!), but has now sunk to 66 to start this season. Okay, guys, something *is* happening.

Rushing numbers correlate with the passing data and are trending upwards. From ‘21 to ‘23, the average game rushing was between 112 and 118 yards. Interestingly, offensive output peaked in ‘20, with an average of 267 yards passing and 125 yards rushing (we’ll blame this on COVID). Teams are averaging 131 yards on the ground, even higher than the ‘20 mark.

Rushing touchdowns are relatively stable at 59 for this season (72 in ‘20), but the explosive runs (any run over 10 yards) are up at 237. This number shouldn’t be a surprise. In modern football, it is harder to score by running the ball. The high water mark in the past five years was 213 (again in 20). Total running plays are back up to their 2020 mark (29), which is ~28 called runs a game. Teams are running the ball, and they are doing it relatively well.

How’d we get here?

The Spread won in 2018, which is when NFL football officially ‘broke.’ Up to that point, defenses were well-adjusted to the ecosystem, which allowed them to play static defenses and single-high coverages. The Seahawks and Pete Carroll Legion of Boom was in the past, but its effect on the football schema, especially on defense, still had a stranglehold around the league.

Cover 3 has always been the ‘king’ of coverages in the NFL, with its man coverage counterpart Cover 1 as the favored way to defend offenses. For generations, this was allowed because of how offenses functioned. Talent, as always, is the most crucial factor in winning and losing in the NFL, especially at quarterback.

Defensively, you either had the players outside to lock down WRs, or you didn’t. Inside the box, a unit must have the best talent or get trampled. Until recently, the only answer defenses had was in their blitz structures. The NFL was more or less a protection-based league, so since the ‘80s and Lawerence Taylor, the 3-4 has been a favorite way to attack offenses.

The structure of the 3-4 allows for multiple positions to blitz the protection schemes. In the ‘90s, Dick LeBeau, the famed Steelers defensive coordinator, added secondary blitz paths to the already popularized Fire Zones in the NFL. Now, offenses had to contend with every position on the field as a potential blitzer outside the field CB.

Over time, the NFL periodically changed rules to allow for more scoring. More offense means more butts in the seats and eyes on games. Points matter, and playing defense became much more challenging. Big physical WRs like the Lions’ Calvin ‘Megatron’ Johnson or the long and speedy Randy Moss were the prototype NFL WR. Big, physical, ‘hero-ball’ type skill sets that could match up with the man-centric style of play, mostly outside near the sideline.

Defenders could patrol the middle of the field as enforcers until recently, punishing any WR who dared come through it. As the NFL moved to protect players and quarterbacks, defenders had to become more skilled. The big brutish box Safety quickly died out. Low-percentage outside throws were dropped for high-percentage intermediate crossing routes, a favorite way to attack Cover 3.

RBs were also the central focus of the offense outside the QB, but only for running the ball into stacked boxes. The West Coast offense, a precursor to the Air Raid, utilized the RB out of the backfield, but it never became a standard way of attacking defenses. Until recently, RBs in the passing game were mainly used as rare check downs or for called screens against blitz-happy defenses.

That quickly changed in 2018, as Spread offenses took over the NFL spotlight for good. This came after the 2018 Super Bowl, where we saw the Eagles win utilizing RPOs and a ‘college-like offense.’ The Eagles’ Saquan Barkley was the last RB selected in the top 5 in the NFL (Giants) in 2018. This past draft (‘24), we didn’t even have a RB selected until Jonathan Brooks went to the Panthers in the second round.

Bijan Robinson went in the top 10 in 2021, and Jamyir Gibbs quickly went after him at 12. Both RBs have unique skill sets that allow them to play WR or RB. The hybridization of offenses has accelerated since 2018. The standards now at the RB position are players like the 49ers’ Christian McCaffrey and the Saints’ Alvin Kamara, two RBs that can moonlight as WRs and are multiple in how offenses can utilize their skill sets. It’s all about matchups, and it always has been.

The RB position has wholly transformed as more offenses shift to Spread schemes. There is now an ‘added’ value needed to play RB. Players like Derrick Henry, who are physically battering rams, are less likely to be taken early in the draft. Not only does a team get diminishing returns from a shorter career, but RBs are now required to catch the ball. TEs are seeing a similar positional arc as we now have three different types: Flex (WRs), traditional Ys (TEs), and blocking TEs (glorified tackles).

Travis Kelce is an excellent example of a Flex TE who is not required to block on every down. The 49ers Kittle is probably the game's best pure ‘Y.’ The Steeler's ‘23 third-round pick, Darnel Washington (Georgia), is an example of a blocking TE who is a matchup nightmare in the Red Zone. He scored on a back-shoulder fade route against the Broncos’ PJ Locke—6’7” versus 5’10.”

Related Content: Field Vision’s Top Tight Ends

Positional value is important, too. Quarterbacks and WRs salaries are far outpacing other premium positions. On defense, Edges are the top-paid players. RBs, LBs, and Safeties tend to be at the bottom of the barrel regarding spending. We saw this offseason several high-caliber Safeties walk into free agency because teams felt the cost outwayed their importance.

Ironically, coaches from the Ravens system quickly pivoted to take advantage. The Ravens, Chargers, Seahawks, Titans, and Dolphins all acquired three starting-caliber Safeties this offseason. The move allows them to play more Big Nickel versus 12 or 21 personnel offenses looking to take advantage of smaller Nickel defenses.

—

» Football’s first predictive analytics app built for the everyday fan. Download it today!

The Trickle-Up

College programs quickly pivoted to the Spread in the early 2000s. The hashes at the college level allowed offenses to take better advantage of speed and space. They also leveled the playing field against traditional powers, who were able to stockpile all the giant human beings required to stop the run. Plus, there are more ‘tweener athletes than linemen to recruit from.

Similar to how new start-ups have the agility to pivot quickly while larger companies are tied down with bureaucracy, or how Napoleon initially used his speed to outmaneuver lumbering antiquated militaries during his time, spread offenses started taking advantage of out-of-dated defensive systems and slower players. Coaches like Hal Mumme and Mike Leach led the Spread Revolution.

Others, such as Rich Rodriguez and Art Briles, would add option elements and further streamline (and quicken) the process. The growth of seven-on-seven quickly followed. The best athletes in the country were no longer playing defense but were placed at quarterback and receiver. The NFL is seeing the fruits of this right now. A whole generation of players has now been produced that doesn’t know what life is like without the Spread.

» Side note: Dutch Meyers at TCU was toying with the Spread in the ‘50s. If you have $5,000, you can buy a copy of his book on Amazon.

A natural adjustment by defenses was to go light and play Quarters. The spacing in Quarters allows the defense to stay ‘even’ against Spread formations, cap verticals, and have a quarterback player on either side of the box. Running quarterbacks are now the norm, something ten years ago NFL general managers and team builders didn’t know what to do with.

Related Content: Cautious Aggression - Defending Modern Football (Book)

The talent pool at QB exploded (though it doesn’t seem like it this year), and NFL offenses quickly adapted. The advancement of analytics also assisted in this shift. Pre-snap motion and play-action have been proven to raise the level of play design and add points, not necessarily tempo. You must slow the game down a bit to run motions and multiple formations.

At the college level, teams quickly discovered that once something becomes standard practice, it is no longer novel. It loses its punching power. One-word calls, blitzing the formation, and split-field alignments were utilized to counter offenses. Tempo units began to struggle as more defenses hybridized and found ways to constrain space and create calls that had answers for spread offenses. There was nothing worse than going three and out in 30 seconds.

Tom Brady and Bill Belichick were ahead of their time in utilizing multiple TEs and slot WRs in their offense. They spread the ball out and utilized option routes to take advantage of lumbering LBs and Box Safeites. Once teams saw the success of the Patriots' offense, they followed suit. It is a copycat league.

Coaches like Sean McVay, who stem from the Mike Shanahan wide-zone/boot-influenced system, found ways around the issues of tempo. The exposure to Robert Griffin III in Washington cannot be overstated. It changed the trajectory of that system to what we have now.

Instead of subbing and waiting to see how the defense adjusts, he utilized 11 pers. and found WRs that were willing to block like a hybrid TE. This kept the defense in a similar bind college spread teams had done; the defense has little pre-snap tells to go off of and must ‘call a play.’ Many times, this meant static calls. McVay also used the no-huddle approach to quickly get the offense lined up and work with the QB until the ball was snapped—like a cheat code for the QB.

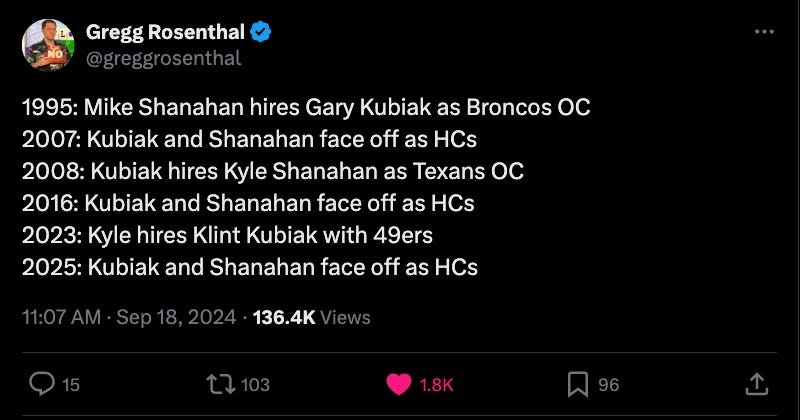

The NFL is now littered with Shanahan or Kubiak-style coaches. Gregg Rosenthal's tweet above illustrates this cycle. Who has the best offense in the NFL through two weeks? The Saints, led by Klint Kubiak. Time truly is a flat circle.

Kolin Kaepernick, Jim Harbaugh, and Greg Roman also can take credit for the Spread Revolution at the NFL level. They proved that you can run the quarterback and that a quarterback who can run can devastate NFL defenses. Lo and behold, who was also Harbaugh’s defensive coordinator? None other than Vic Fangio.

In 2018, we saw our first true ‘Spread’ game as the Rams outlasted the Chiefs 54-51. Andy Reid and Sean McVay single-handedly ushered the NFL into its Spread Era. There was no turning back.

Time is a Flat Circle

We've now hit the point where the metaphoric pendulum swings back. Football has (forever) had a natural cycle. Offenses start to spread out; passing becomes more explosive. Defenses adjust by putting lighter players on the field to match the space. Offenses predictably condense and run the ball.

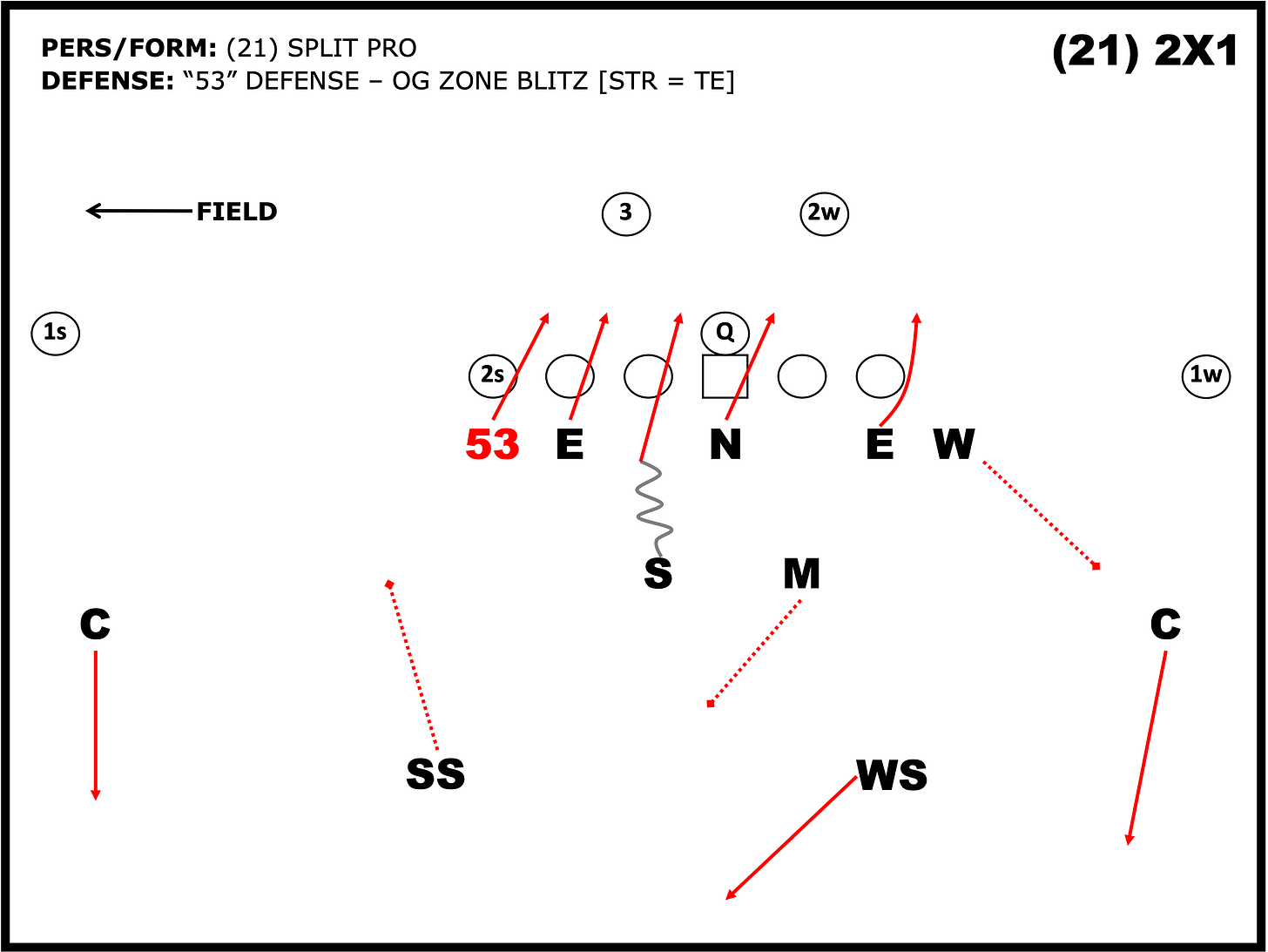

We first saw this in the ‘70s. Teams were getting better at passing the ball, and defenses needed an answer. The Dolphins’ Bill Arnsparger invented a way to ‘safely’ pressure offenses using hybrid LBs to create the precursor to the 3-4 defense. The first was Bob Mahteson, #53, which led to the vaunted ‘53’ defense. Until then, no one had really thought about dropping a DE into coverage while overloading the opposite side with pressure. Thus, the Fire Zone, or ‘safe’ blitz, was invented.

From there, we got the ‘80s 3-4s and Lawerence Taylor. To counter Taylor and the use of advanced pressure packages, the Redskins’ Joe Gibbs devised a way to place a hybrid TE/FB on the field and move him to where he needed extra protection. The adjustment limited the impact of Fire Zones and allowed his on-ball TE to go out for a pass. The H-back was born, and 12 personnel was the trend. Interesting…

As passing became more important, offenses got lighter and quicker, utilizing more 11 pers. In the ‘'90s, we get the invention of Bill Belichick and Nick Saban’s legendary Rip/Liz Cover 3 match, which is the backbone of SEC defenses to this day.

The typical evolution for the defense was to get lighter at LB. The Tampa 2 heyday of the 2000s was a direct result. The issue? Teams went back to compact power-run games, and the NFL crawled back into the cave of offensive darkness.

Related Content: Hybrids - The Making of a Modern Defense (Book)

That all changed as more mobile quarterbacks entered the league, and offensive coordinators at the NFL level got tired of not scoring points. Information sharing during collegiate offseason scouting quickly led to advancements in offense, which we see today. The Spread won, and in 2024, we are now in the beginning parts of the post-Spread Era.

One major defensive trend was using more Nickel packages, which started becoming the norm in the 2010s. Nickel is ‘Base’ in the NFL. Passing was now easier with more rules from the NFL front office limiting the ability of defenders to stop WRs near the line of scrimmage, and it was strictly enforced. DBs had to be more skilled, and WRs could be smaller, quicker, and more savvy about their route running. Offenses now had relatively free access to space.

The NFL's coverage landscape has drastically changed in the past five years. Cover 1, a staple concept in the league, has dropped below 20% for the first time ever. It was at 30% of coverage calls in 2019. After the 2018 season, defenses doubled down on Cover 1 because it is an ‘easy’ answer for RPOs and limiting free access. The problem is that all the pressure is on your DBs at all times. It was a recipe for disaster.

Then, in 2020, we saw something truly startling. The Broncos (Fangio) and the Rams (Brandon Staley) started running their defenses from two high shells over 80% of the time. That was unheard of before that season. The system was built to stop the highly potent spread attacks beginning to populate the NFL, and it worked.

As explosive passing numbers started to drop, and QBs were forced into being ‘check-down Charlies,’ more defenses shifted to this approach to stop explosive passes. The Fangio system has been around since the 1989 New Orleans Saints. Vic Fangio and Dom Capers were on that staff. Dick LeBeau would learn the system working as the DB coach under Capers in Pittsburgh. The most influential playbook in the NFL came from this time. Even the Ravens system, which Mike Macdonald has revamped, has its roots here.

Fangio took the system and retooled it, adding the two-high pre-snap shell. His time with Harbaugh and Roman helped him develop more tools for coverages to counter mobile QBs as well. Ironically, the system's issue is that it isn’t great at stopping the run consistently.

Fangio’s scheme utilizes Cover 2 and Quarters together and is not a ‘Qaurters’ system, nor a Tampa 2 system. Instead, it mixes weak rotation Cover 3 and Quarter-Quarter-Half iterations to mask the secondary's intentions, even using match (think man with rules) principles in its zone coverages. QBs and OCs often can’t tell the difference until they watch the film the next day.

The McVay/Shanahan tree has recently popularized under-center play-action and wide zone. The Fangio system was uniquely built to take advantage. The two-high structure assists versus motion and crossing routes common in the system. It also forces the quarterback to recalibrate their passing cues post-snap as the bullets are flying. Bill Belichick utilized a Quarters structure similar to Fangio’s to stifle the ‘18 Rams offense that looked unbeatable.

Fast-forward five years, and more teams are running Quarters and split-field coverages. Baltimore is another dominant defensive system that has been retooled, updated, and streamlined. We saw a run on their defensive coaches this offseason. Safe pressures and split-field coverages from Nickel defenses are now the norm. As we know, once something becomes standard, the other side pivots. Time is a flat circle…

The ‘Obvious’ Answer

What is the one best practice all offensive coaches know regarding attacking two-high shell defenses? Run the damn ball.

It’s a simple math problem. The defense has to allocate more numbers in the secondary, which limits the numbers in the box. Those number advantages tip in favor of the offense, who now has their $50-60 million quarterback turn to hand the ball off. But there is a problem with that statement, and it has to do with money.

Why hand the ball off to a RB who is a fraction of the worth of the team’s QB? Efficiency. Still, most OCs understand that throwing the ball is more explosive for the offense than it is to run the ball. A five-yard run is a five-yard run, but a five-yard pass can quickly turn into a 50-yard touchdown; ask anyone who plays the Dolphins.

Still, offensive numbers are down, and pundits are scratching their heads. Where did all the points go?

One simple answer is game control. There is no reason to keep throwing deep passes into the secondary when the defense is already prepared for them. This is why we see more Escort Screens, where offenses send a blocker to assist the check-down option. If the defense will give it to us, we might as well enhance it.

Running the ball is still very important, and it appears OCs are finally leaning into the soft spot of modern defenses. The adage is: pass to score, run to win. That still rings true. Football is a physical game; running the ball, especially when winning, is important to the team’s success. We are also in a defensive era where offenses can take advantage of box numbers.

It isn’t just about running the ball but how you do it. Pre-snap motion, varying points of attack, and steering clear of obviously stacked boxes on early downs help the offense stay ahead of the changes. Think of running the ball as body blows in a boxing match. A boxer accumulates them until the one final haymaker to put their opponent out. That is the passing attack.

So, why are numbers down for offenses through two weeks in the NFL? Again, it's simple math for both offense and defense.

Do you want to die fast, or give yourself a chance and die slowly? Forcing teams to run the ball gives you a chance to win. Unless you can’t stop it… Then nothing matters.

Running the ball not only slows the game down but requires muscle. Fewer plays equals fewer drives, which leads to fewer points. Offenses are beginning to shift to heavier personnel, too: 12, 13, 21. Light (Nickel) defenses are now caught in the middle; they still have to defend the pass but are getting hammered in the run game.

This past offseason, we saw several interior defensive linemen get paid. These humans, in particular, are impossible to find, and when a team does, it needs to pay them and hold on to them for dear life. The reason these players are so critical in the modern game is run spacing, which is a fancy coach-speak phrase to illustrate run fits. When playing from a two-high shell or split-field coverages, a defense has one fewer defender in the box.

The defense needs a strong core in the middle of the box to counter that limited number. Edges are a premium, but sacks are overrated. Occupying three offensive linemen with two defenders (four down) or four O-linemen with three iDLs (odd front) tips the advantage back to the defense. It also allows the defense to allocate more numbers to the pass.

The dichotomy of modern defense is the ability to secure the run game (box) while allocating more numbers to the passing game. Again, we have math on our side. I have the advantage if I can put seven in the pass distribution, and the offense can only send out five.

As the Seahawks’ Mike Macdonald tells his defense, ‘Stop the run, to have some fun.’ Control the game with the front to win early downs. Win early downs to dictate protections and get after the quarterback on 3rd Down. Just like offenses use the run to control the game, defenses must stop it to change the math on the back end and earn the right to pressure on passing downs.

The ability to keep the RB, who is now most likely a dangerous WR, in the box to block shifts the numbers in the defense’s favor. Simulated pressures ‘trick’ the offense into keeping more players in the protection, but the defense doesn’t lose its ability to cover. These are even ‘safer’ pressures than Arnsparger ever dreamed of. A simulated pressure (sim) gives a pre-snap appearance of rushing five or more, only to drop out defenders and rush four.

Still, the interior of the line has to hold up. Chris Jones, Dexter Lawrence, Quinnen Williams, Deforrest Buckner, and Derrick Brown (to name a few) are critical to their defensive unit’s success. DJ Reader’s presence in Detroit has amplified the play of Aidan Hutchinson, who currently leads the NFL in sacks (5.5) and has a win rate of 42.3% (min. 15 snaps).

Losing that one guy can get ugly as the Safeties now have to play from depth to make tackles, or the offense is ripping off 7-8 yards gains up the middle consistently. All of those options are demoralizing. Remember when the Rams played with a one-armed Aaron Donald in the playoffs against Matt LaFleur and the Packers? Yeah, it didn’t go over well.

The Chess Match

The Spread Revolution has won, and we are not returning to the smashmouth days of the '90s and early '00s. Football has become a space sport. Still, offenses utilize their advanced knowledge of space to gain an advantage in the run game. You throw to score and run to win. Defenses are now left holding the bag with a third CB on the field instead of a LB. Either case can be an issue in today’s game.

NFL defenses have become skilled at eliminating explosive plays and compressing the field. Quarters and split-field coverages have become increasingly popular in the past five to six seasons. Teams can now cap verticals, eliminate free access throws, and force quarterbacks to 'work.' Even Patrick Mahomes has struggled at times to find open WRs downfield, making the best QB in the game a checkdown guru.

Keeping the Safeties at depth allows them to see Deep Crossing routes early, cut them off, and eliminate them. Backside Digs and Glance routes off play-action are also eradicated because the Safety is sinking through that zone post-snap. These aren’t quick movements but information-gathering steps to decipher run or pass. As a DB, playing down is much easier than playing back, where your eyes can get you into trouble and late to the deep intermediate zones NFL offenses love.

Offenses have countered, though, by utilizing more TEs, FBs, and heavier personnel groupings, which in turn force the defense to stay in Base structures, drop Safeties, or find slot defenders who excel at stopping the run and can play coverage (rare). This is why we saw a run on Safeties this offseason. Welcome to the next evolution of professional football.

Defenses are also finding ways to create ‘formations’ to counter QBs and OCs who love to pick from a highly curated list of plays to oppose defensive personnel. It used to be that defenses lined up and played, only sparingly utilizing coverage disguise. Blitz disguise has always been around, as has protection manipulation by alignment, but now we are seeing coverage and front disguise paired together. What you see isn't necessarily what you get, which compounds issues for the offense.

Modern defenses, in 2024, have to be multiple in their approach. With limited time to teach players, NFL DCs are stealing from their college counterparts. Adaptive defenses that are customizable and flexible are increasingly being used. Static structures will mostly get you beat, even if you have the best talent.

Coaches must contend with various players and formations on any given week. With a limited number of roster spots and money being allocated overwhelmingly to the offensive side, DCs will need to be creative and better teachers. Talent is king, but it is also scarce.

In 2020, the Fangio-adjacent system became popular. The system runs most of its defense from a two-high shell and uses weak rotation Cover 3 and split-field coverages to mask intentions. The use of similar (not the same) concepts muddies quarterbacks' reads. Average quarterbacks now have to process information as the defense barrels down on them. Hesitation spells death in the NFL.

Using a two-high shell protects the defense from shot plays and forces the quarterback to work through their reads post-snap. It also constrains space down the field by playing zone instead of man. As play-action became popular, defenses shifted to a two-high shell for leverage and disguise. The result was lower scoring because quarterbacks were forced to throw lower percentage throws or utilize the soft areas underneath, where zone defenders rallied for the tackle.

Fangio's influence on coverage has made it more difficult for quarterbacks to decipher what they are getting. Suddenly obvious answers like Glance route RPOs behind a down Safety and Y-Cross (versus anything) are now non-optimal. The days of Aaron Rodgers and Peyton Manning sitting in static formations, reading the defense, and attacking the space downfield are gone. Context clues aren’t always what they seem anymore.

Offenses are utilizing pre-snap motions to get defenses to show their cards, but even that can sometimes lie. Defenses are now better equipped to handle man/zone indicator motions by retooling their zone coverages to look like man coverage. This, in turn, also lends itself to utilizing split-field structures that are 'even' and less affected by these quick motions. The constant cat-and-mouse game has created the game we see right now.

Teams are also employing hybrid off-ball LBs to create different front structures without allowing the offense to get a bead on what they are doing on a down-to-down. The use of an extra Safety matches the hybrid TEs on the field while still giving the defense the schematic flexibility to run Nickel.

Defensive ‘formations’ are real, and jumping from odd to even spacing (run fits and structure) or vice versa is critical for modern defensive success. Even coordinators who have been relatively strict about alignments are dabbling in this idea.

There are other factors for the lack of offense outside defensive structures. Offensive line play has been a hot topic for the past several years. Less time for practice at the NFL level and a college environment that favors RPOs, quick-strike passing, and zone blocking have resulted in less development of the offensive line. Teams now use preseason games to give playing time to backup players and assess those further down the roster. Offenses only get live game experience if their teams have joint practices, and even then, it is a carefully coordinated process. It's no surprise that offenses are starting games more slowly as a result.

We are transitioning from the NFL's Spread Era to its new iteration. Offenses are not ditching the pass (for now) and being more thoughtful about when to throw it. This is still a QB-driven league, but OCs are quickly shifting to building robust run games to counter light defenses. Let the games begin…

—

© 2024 MatchQuarters | Cody Alexander | All rights reserved.

Do you think any of the Chadwell Gun Triple stuff will start to be seen in the NFL?