Re-Examining Opponent Breakdowns

The Problem with Over-Reliance on Numbers and How to Approach Offensive Opponents Holistically.

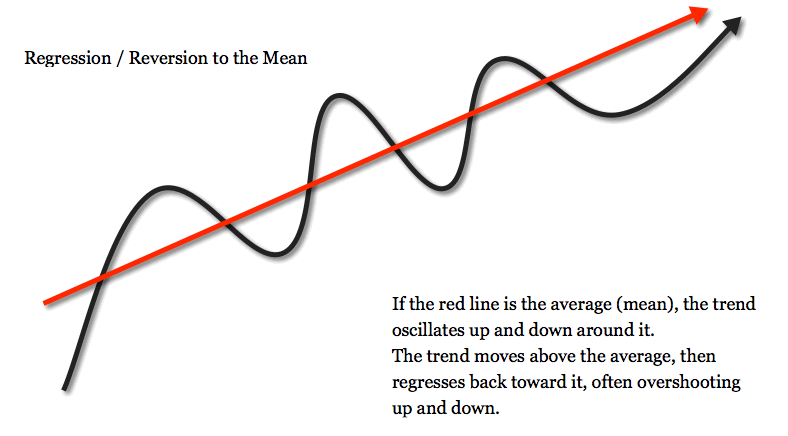

There is an over-reliance on numbers or percentages when breaking down offensive opponents and developing coherent game plans on the defensive side of the ball. In most cases, defensive coordinators try to regress everything to the mean. What is the offense doing on any given down at this specific position on the field? That is such a narrow question for a side of the ball that is reactionary in nature.

The problems for defensive coaches begins at the start. Too often, in game planning, the staff looks from the starting line instead of from the finish. Instead of looking backward and asking, ‘What is the offense doing consistently?’ defensive coaches say, ‘What are we going to get in [insert scenario]?’

Similar to the image above, offenses oscillate throughout the year depending on the defenses they face. Football is a space sport, meaning the offense tries to create space for its athletes. The lower the level, the more likely the offense will use more space to create an advantage. This is why the 10 pers. Spread is still popular at the lower levels, especially when an offense has an ample number of athletes.

The main objective of the offense is to create space. Defensively, the main objective is to constrain it. When looking at game planning from a big-picture view, too many numbers can skew the data. Not every defense is the same, but the offense you are playing has a base, and rarely do they deviate too far from it.

A team's base offense will stay the same regarding play selection from Week 1 to the end of the season. Sure, injuries can affect the scheme, but looking at it objectively, offenses have a core set of rules they want to implement in any game plan. Each week, that game plan is tested against a completely different defense.

To affect the defense, offenses use motions, shifts, and formations to create advantageous leverages and matchups. Defensively, a coach has to react to those tools. A static offense allows the defense to adjust quickly, and a well-formed defense has plans for these motions.

Numbers can be great, but defenses often look at tendencies within a 50-60% range. Therefore, as a staff, you must define a tendency. Is the magic number 70%? Those are rare. If you have a significant tendency in the 80-90% range, plan accordingly, but in your back pocket, think of ways this offense can counter through self-scout.

Most coaches will place as much data as they can in columns and then create a bunch of printouts so they can look at the data. Over the years, I started to find ways to make these data points more concise. Information is great, but if you are wasting time looking at thousands of data points, and only 100 of those will help you, you are wasting a lot of brain power and energy that could be used to develop a more comprehensive game plan.

A powerful platform used on Microsoft® Visio & PowerPoint to allow football coaches to organize, format, and export Playbooks, Scout Cards, and Presentations efficiently.

One of the best things a defensive coach can do is to sit in a clinic with a highly successful offense coach. I started to look at game planning entirely differently when I listened to the former Head Coach at Rockwall, Guyer, and the current leader of Rockwall-Heath, Rodney Webb. The way he explained how they formulated their plan of attack was so simple that it made me analyze why I would dig so hard into thousands of data points. In reality, I was looking for a needle in a haystack.

In Texas, at the higher football levels, the 11 pers. Spread offense is a staple offensive structure around the state. Spread, in Texas, is king. With that, there are multiple varieties, from the Gus Malzahn/Chad Morris system to the extreme uber-spread formations of the Briles system and every variation in between. In each system, how they react to different front and coverage structures varies.

Coach Webb runs an 11 pers. based offense with a high volume of RPOs off different run looks. In Texas, the 10 pers. Spread is not very popular at the 5A/6A levels. Offenses opt to run more two-back or Y-off formations with three primary wide receivers. Non-garbage time1 passing numbers would vary each week depending on the coverage played. So, when analyzing percentages, you look at the mean amount rather than what your defense might get.

The hurry-up no-huddle is also popular in Texas, and Webb’s teams would use it to keep defenses static and to target space on the field left open by misalignment. Over the years, teams have adjusted their tempo philosophy and varied their speeds to throw more looks at a defense. These looks, or formations, dictate the alignment of the defense.

Webb explained that they generally only used about five different run concepts and ten different passing concepts (non-RPO) in their game. That seems simple and easy to handle at the surface level, but Rockwall had a twist. They would create new formations and motions to pair with these plays each week.

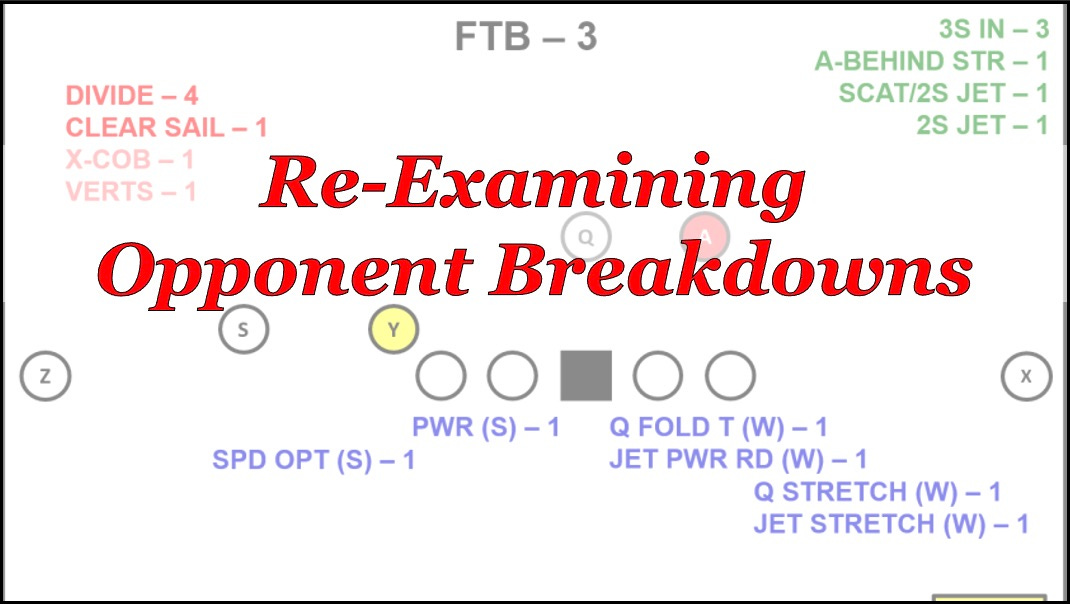

To the defense, what they saw one week differed from what they would get the next regarding formations—the illusion of complexity. Defensive coaches would get all their data points watered down because each was tied to different formations. Rockwall still ran traditional formations, but they would dress those up with motion or move a player to a different spot. What looked like a simple Hit Chart2 was amplified by multiple formations over multiple games.

I always followed a rule of three: if the formations were ‘normal' and not unbalanced, I discarded them. I’ll explain later how I used this data. Webb and his staff devised a way to look multiple in formation but keep their game plan simple so the players could play fast. They would use tags and motions to counter how the defense aligned.

Sitting back, I had an epiphany. Why was I wasting time on completed formations rather than breaking them down to their roots? Let me explain.

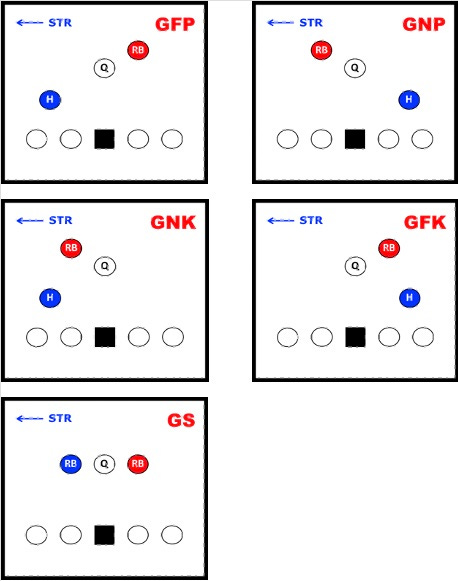

If an offense comes out in a traditional Y-off formation with two WRs to one side and another on the other, they can still create multiple formations just off-back alignment. Each one makes a new sub-section of the root ‘Set.’ Each image above would be labeled as a completely new formation. The offense could create five different formation tags without moving a WR, and they could still run Pistol!

When labeling every minute detail, the percentages and tendencies can muddy the information, but now you have to wade through even more data. Webb’s explanation of how his staff game planned enlightened me on the redundancy in my approach to breaking an offense down. I started examining everything, from how I labeled formations and play calls to the columns I used.

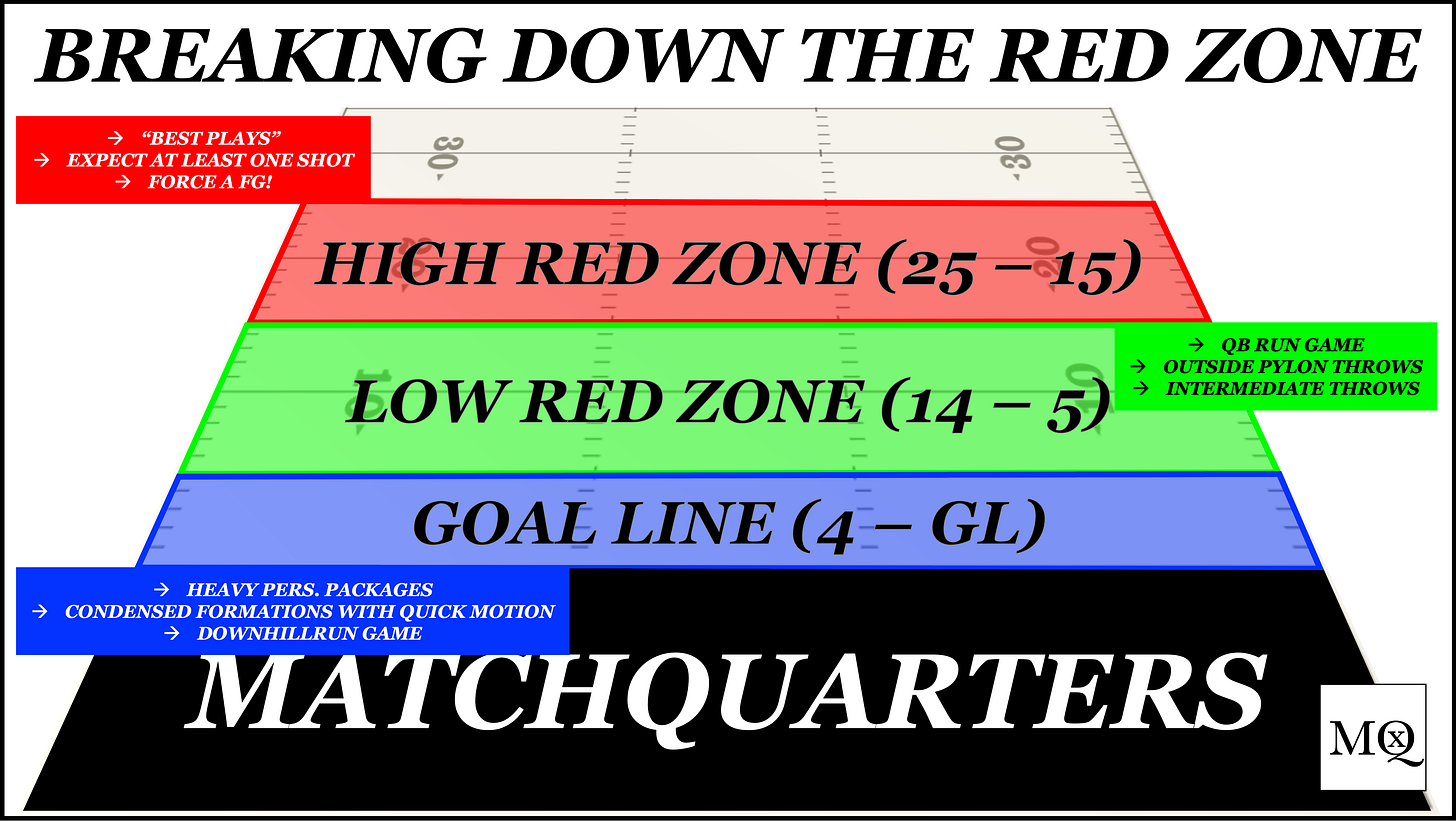

I boiled my columns down to the above. At the front, you have your typical Down, Distance, Hash, and Yard Line. Those are standard and help you break the play calls down into Field Zones and specific Down & Distances (D&D), which are critical for calling a defense.

From there, I labeled the personnel, Set, total formation, if the passing strength was into the boundary (FIB), motions/shifts, Run/Pass, Tree (where you label RPOs), Play, and Back Side Concept. Adding to the play structure, I wanted to know if there was a Deep Shot (throw over 15-20 yards), who was the main target, and play direction (Right/Left). Finally, you get the result and gain/loss column.

These gave me all the information I needed. When facing a team that runs different formations each week, you can cross-check root formations with the Set column. If you often have a million formations and check the Set (2x1, 3x1, 2x2, etc.), you can better understand how the offense is game-planning.

The team above had pure backfield tendencies and always stayed within Twin Open (2x1). When they ran Gun Split (both backs beside the QB), they ran Split Zone (Whack). When they went to Pistol Far (H-back away from the passing strength), they ran Zone Wrap (lead blocker bypasses the DE, QB reads the DE). The offense was very static; there was no motion. This team was easy to game-plan for.

When devising a plan, most of our calls would be formational-based. We wanted to attack the backfield set, not the overall formation. But, most offenses are more challenging.

Percentages and numbers are great when you have concrete data. Most offenses, especially the flavor-of-the-week ones, don’t give you that. Defenses are reactionary and must adjust to what they get from the offense in real-time. We get convoluted and watered-down data when presented with constantly changing formation and motion data. That is why it is vital to carry a safeguard in the way you label the offense.

When staff section out scenarios and field zones (Red Zone above), these data points can get even more convoluted. One thing that helped me was to look at sets, motion use, and the root plays. Sometimes, teams would run shorter routes and shift to more of a power run game as they got closer to the end zone, while other teams didn’t change.

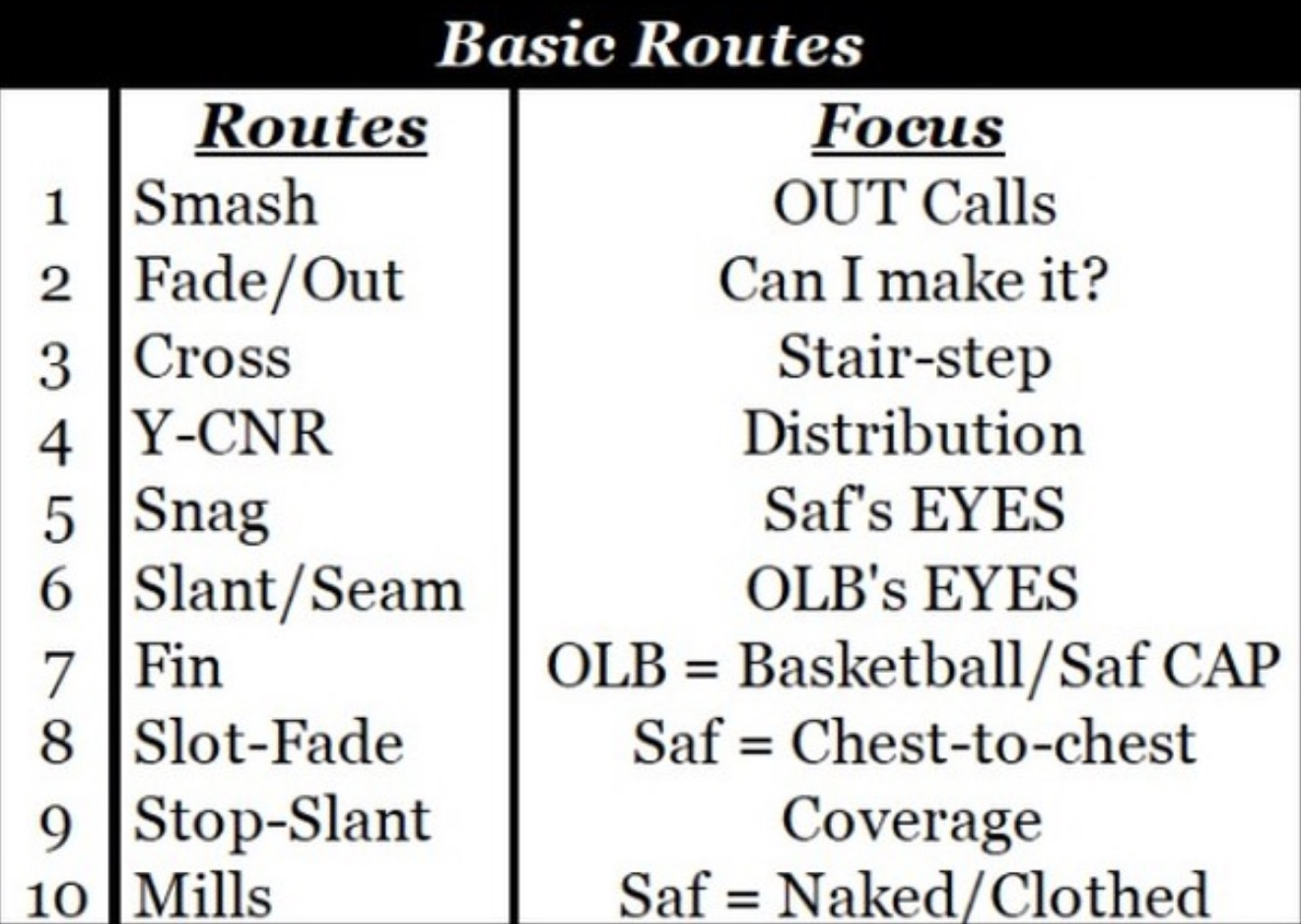

When I created a game plan, I wanted to know what the offense wanted to do, not what kind of eye candy they would throw at us. I would list the main route concepts we would face each week, like the one above. Most times, when I broke down the main two-man route concepts, I couldn’t even get to ten. In that case, we worked on ‘problem’ combinations (everyone is a copycat!).

In the run game, it is usually even more straightforward. The offense you see will typically be based on the zone or gap scheme. From there, they will usually only carry about five different concepts. » You work on those.

But how do you line up, and what do you do about motions? I believe in teaching Sets; from that, you get alignments: Stacks, Bunches, TEs, and Wings. When approaching game planning, I like to look at it conceptually. If an offense is static, we as a defense have an advantage, but most offenses tend to lean towards changing things up each week.

When teaching game plans off-set and not traditional formations, your players see the game in easy-to-determine numbers: 3, 2, 1, & Quads. The offense can only have five WRs out, so there is always a mid-point. Motions either create leverage (quick/push) or change the Set. Each week, we would work the motions in the secondary that we would see; most can be boiled down into three categories:

Short motion - Doesn’t change the strength call

Quick/push motion - Uses speed as a leverage but doesn’t change the formation

Across motion - WR shifts from one side to the other and can change the strength.

Shifts are relatively easy to handle, especially if from the TE. You can use line movement or simple D-line shifts to reset the front. The change of strength motions needs to be worked on, and most defenses have upgraded their systems to handle them. Whether you are a Ni-travel or pull-the-chain system, most philosophies can handle them. Pressure design is where it can get tricky, and that is why I always drew them up before we presented them to the players.

Formations set the stage, but the real actors are the plays or the plan of attack from the offensive coordinator. Similar to the flavor of the week formations, you can gauge an idea of a game plan of the initial script by the OC. I call this The 15-Play Rule.

All OCs should be judged on their production after their scripted plays. Typically, this is where you find out who is a coordinator and who is a playcaller. Making a cut-up of the first 15 plays gives insight into how the offense wants to play the game. After those plays, the OC reacts based on your alignment and your game plan.

I would track the first 15 plays of the game weekly, see the shifts, motions, and formations, and generally be able to tell what they wanted to do the rest of the game. This is why your overall plan needs to be simple to start, then pull answers from your toolbox. You will be lagging in your thoughts if you are bogged down with data points on every D&D, personnel grouping, and field zone.

There is a fine line between too much data and needing more. You are defending formations and mitigating risk. Who are they trying to get the ball to? Where is the ball hitting? Do they have tendencies at specific points in the game? Again, everything regresses to the mean, which is where you should be in your game plan. For instance, if a down is 50/50, then your pressures and thought process should be centered around needing a call that adjusts to the run and pass.

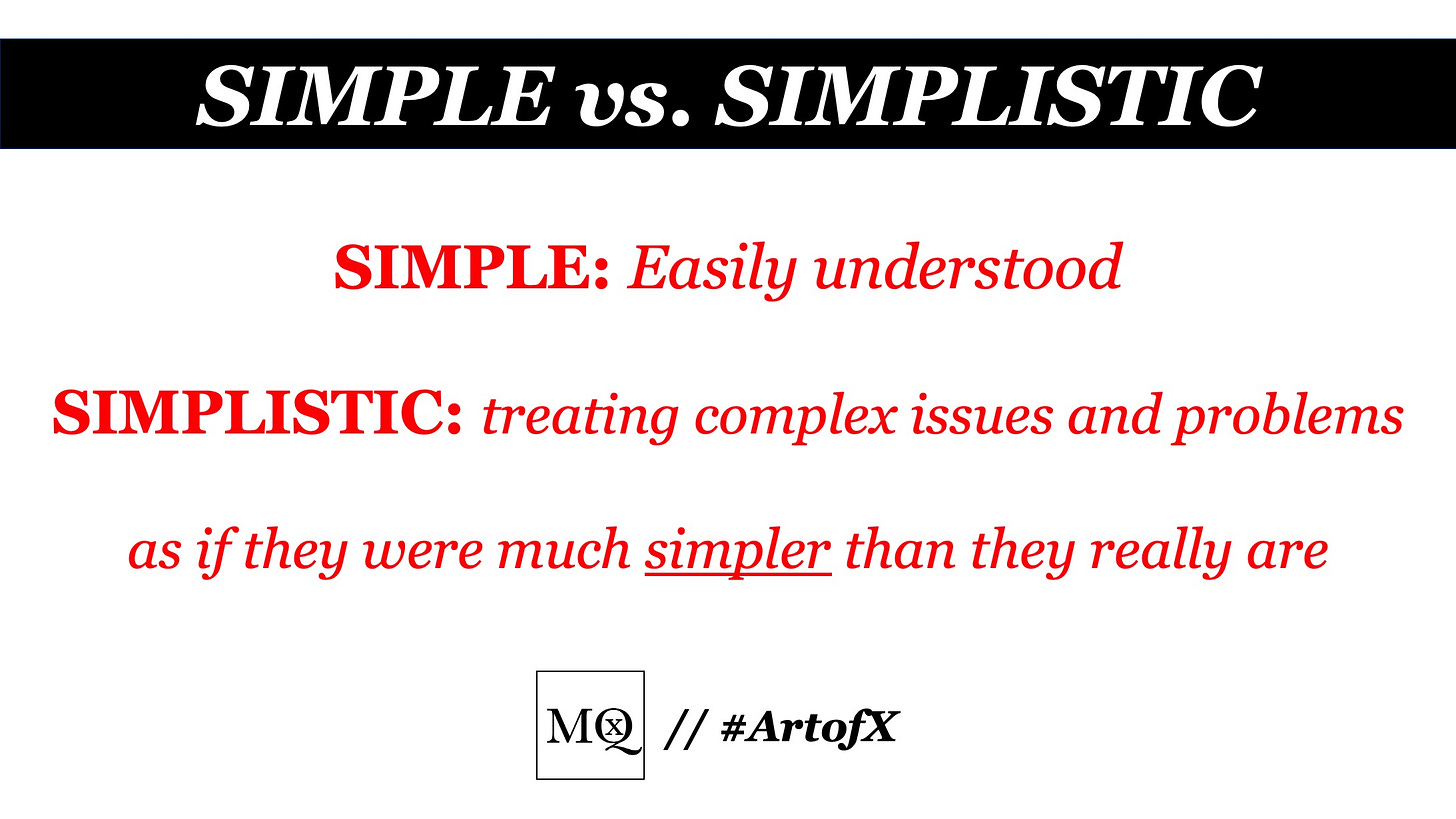

Keep your process simple but not simplistic. Think of it as creating one-word calls; you must still teach the structure. The ‘sentence’ or long call allows you to play the one-word call. In opponent scouting, you still need your data points, but you can accelerate your game plan process by distilling the information at first and then digging deeper if you still have questions.

Last year, I heard an offensive coach talk about how they ran Y-Cross 15 times in a row during a game but changed the formation and motion every time to make it look different. His players only had to adjust to the new spacing, but the concept was the same. The coach then amplified the scheme by tagging different routes away from the root Y-Cross to manipulate the coverage they would get because of the new formation.

As a defensive coach, looking at that statement made me realize that I might have labeled every one of those plays differently if I didn’t have safeguards to distill the information. This is why I believe in splitting the field when labeling past concepts. If it is a full-field progression concept, I will mark that as the core offensive play, then label what the routes were away from the primary read. Doing this allows me to see how they are trying to manipulate the secondary.

Some defenses are different, too, and offenses will adjust to what they see each week. For instance, if you are a man coverage-heavy scheme, it probably wouldn’t benefit you to work Quarter's beaters all week, and vice versa. Run game calls will also change depending on the front structure. Generally, teams will block plays differently when presented with Tite than with a base ‘G’ Front in a 4-2-5.

Because defense is reactionary, there is a tendency to chase ghosts and the stress of trying to add enough to defend everything. The result in that is usually information overload or paralysis by analysis. Quality information and data points are essential, and you still need to have some sort of data entry process, but when you get that data, start at the end. What do we actually have to defend to be successful? Not, ‘How do we defend everything?’

In conclusion, looking into the past can get you into trouble. I always liked to break down the three most recent games and then one or two prior games with similar defenses. Many times, if this was a team we played the previous year and the staff had stayed the same, I would include our previous game. When you utilize too many games, you can get too many data points, or what I call ‘junk’ data, because teams don’t play your defense.

In most cases, offenses will see how you react to a formation or motion, then, within their scheme, create ways to replicate it. We have all seen the copycat offense, where the OC runs the ‘good’ plays from the week prior against your defense. Those offenses are even more chaotic to break down, but because they don’t have a base, they are usually not successful.

Use the data you have available and project it into the future. Think like an OC. How would they attack our defense knowing what they’ve done in the past? Above all, always remember ‘players over plays;’ the offense wants to get their best player the ball, make them left-handed.

—

» If you are looking for a comprehensive opponent break down resources or want to revamp your process, I have a book that goes into more detail on the topic:

Breaking Down Your Offensive Opponent

—

» I also have several templates to help your staff and you streamline the process:

© 2024 MatchQuarters | Cody Alexander | All rights reserved.

Garbage Time: moments of a game when the outcome has been decided. Usually, the lead is by 28+ points, or the team has subbed their starters out.

Hit Chart: Diagrams of all the formations an offense runs and what plays were run from them, usually broken up by personnel group and final formation.

Awesome stuff, Coach - thanks! I do find the challenge of opponent breakdowns to find a signal in the noise that makes them predictive rather than only descriptive, especially when facing teams that vary their attack from week to week. And to not get bogged down in the data as you note!

Love the idea of reducing down a layer to sets to avoid getting lost in each formation iteration. For both sets and formation, do you tag pre- and post-motion? Obviously where the players are at the snap is the most important but I don't believe Hudl Assist tags the final position.

Also when you tag personnel, how do you think about player type vs pure formation? Ie in HS often TE is a wildcard and when grouped with 3 WRs / 1 RB, the same kid could be aligned as Y-on in 11, split out in 10 or in the backfield as a sniffer in 20.

Find your content incredibly valuable - thanks again!

Thanks, coach. I think there was something in this article for everybody, coach and fan alike!

Can you share what the two-letter acronyms mean under your Form category? I assume GS is Gun Split. But uncertain about TW and OP.

Also, how do you balance charting out an opponent’s philosophical base (Xs & Os) with time spent evaluating their players’ talent (Jimmy’s & Joes) and potential mismatches?