Mike Macdonald’s Pressure Masterclass at Super Bowl LX

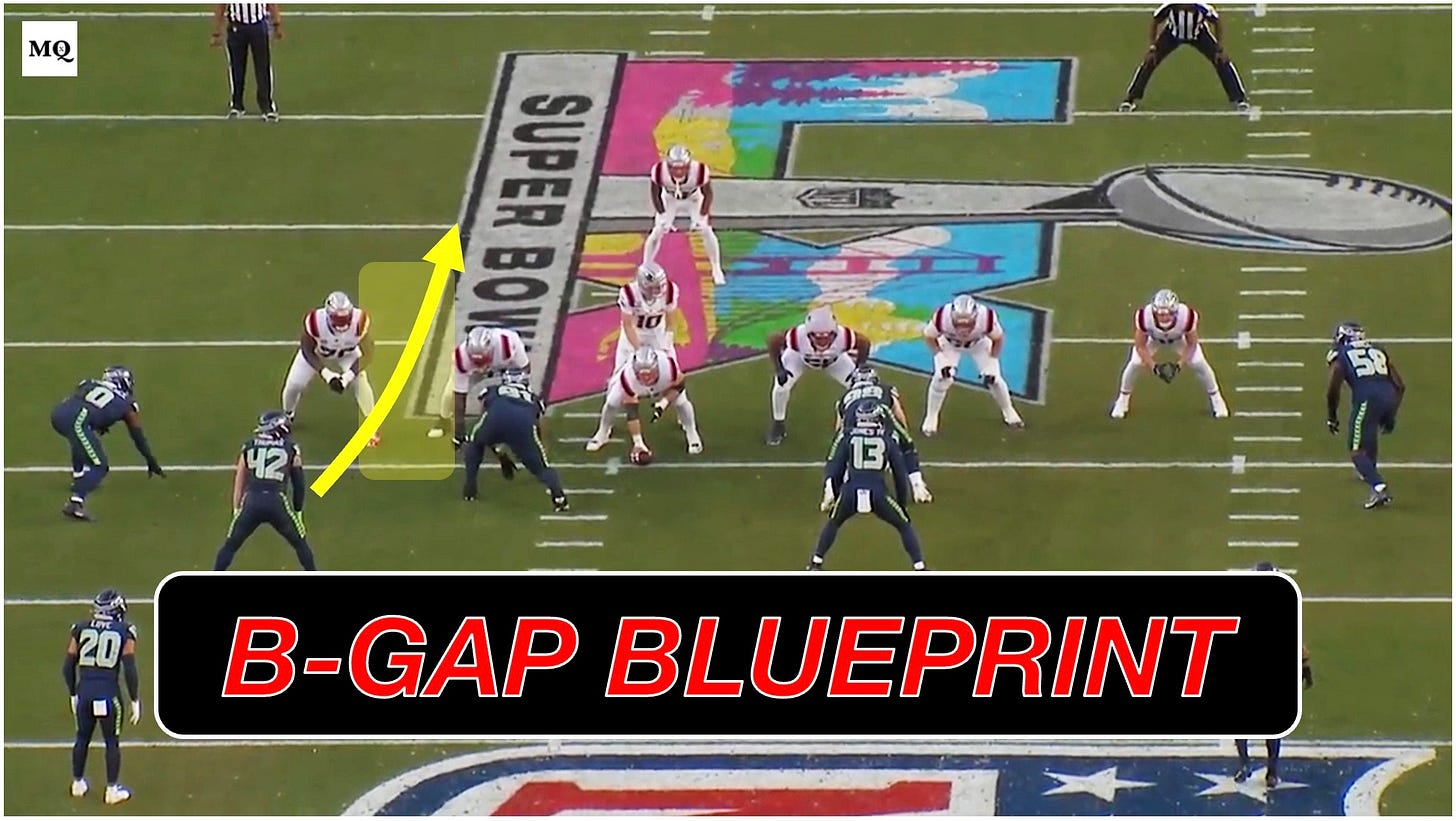

How the Seahawks utilized "Passive Pressure," B-gap "Stabs," and "Stride" paths to dismantle the Patriots' offense.

Last year, it was all about Quarters squeezing the air out of the target-rich intermediate zones and the Eagles’ dominant defensive line. In this year’s Super Bowl, the game centered on another dominant D-line, as well as sniper-like blitzes from the second level.

For over five years, we have become accustomed to the Chiefs’ Steve Spagnolo wreaking havoc on opposing offenses as he calls preternatural blitz checks that always seem to hit home. In 2026, Mike Macdonald didn’t just take the torch from Spagnuolo; he evolved it for the new NFL meta.

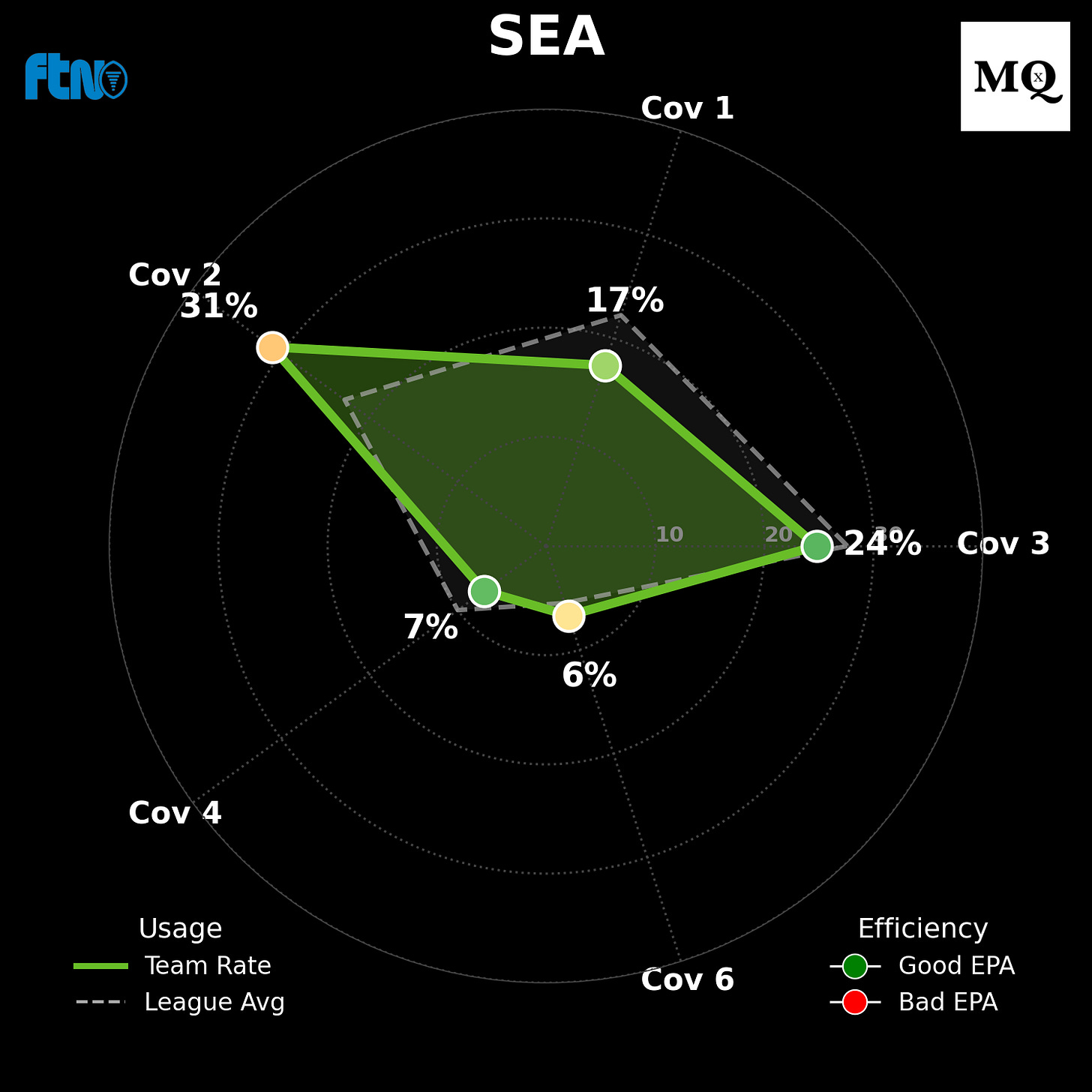

Throughout the NFL season, the Seahawks have held the league’s best defense. The unit is a clear example of how a modern defense should function and appear. One of the key aspects of the Seattle structure is its ability to stay not only in its “Big” Nickel package but also in a two-high shell.

Even 49ers Head Coach Kyle Shanahan pointed it out pre-game:

I know you guys want my expert opinion, but I haven't scored a touchdown on these guys last two times we played 'em… I mean when you just look at this film… this is what they stay in all day. Right? They want to have two safeties that are deep. It's a huge challenge. You can't stay in this defense very long and stop the run, but they do.

Shanahan went on to lament that even if you get the coverage defenders to move, you still have to deal with the pressure. Seattle’s design under Head Coach Mike Macdonald enhances the players on his roster while squeezing the life out of the opposing offenses.

The two-high shell compresses the field and floods the intermediate zones, while the front four changes the math in the run game. Macdonald’s defense features a typical four-man front, but the interior defensive line of Leonard Williams (99) and Byron Murphy II (91) typically forces double-teams.

When the defense’s two interior players require three or four blockers, that allocation changes the math in the run game; the numbers are now tilted toward the defense. The Seahawks can play with a six-man box, and the final piece, the Nickel, arrives late for support.

Nickel Nick Emmanwori (3) and Will Linebacker Drake Thomas (42) serve as leverage tools in the run game when offenses try to get “big” or add a TE to the box. Seattle rarely comes out of their sub-package defense (~91%); they ran their “Base” 3-4 on only ~6% of their downs, a league low.

Seattle is “attacking” offenses, but it is subtle and nuanced, something I call “passive pressure.” It is not that Seattle doesn’t blitz; they just conserve their ammo. Macdonald has become a “sniper” in the way he calls a defense. The structure and compression of the defense are more important than the overall raw power of their blitz package.

During the regular season, Seattle only blitzed on about a quarter of their plays. That number was even lower on early downs (1st/2nd). The only down where the Seahawks really got after opponents was on 3rd & Long, where they had a Blitz Rate of 40% (10h).

In the Super Bowl, Macdonald flipped the script a bit. Instead of playing a “passive” game, he took it to the Patriots’ offense early. According to Sumer Sports, the Seattle Blitz Rate in the 1st half was 33% compared to their 2nd Half rate of 8%.

Macdonald chose to end the game early and take advantage of tendencies from the Patriots by blitzing certain looks. After the game, hybrid CB Devon Witherspoon (21) laid the game plan out for Sirius XM NFL Radio’s Kirk Morrison:

Witherspoon: We had a good tell on what they like to do and how they like to play, and how they were going to attack us. So, you talk about a coach who put us in the best position to win—that’s our coach right there. And that’s why we stand beside him and that’s why we’re always going to have his back.

Morrison: But you’re taking one of the best corners on the field and you want to keep him in coverage, but you were one of the best blitzers today. Why was that?

Witherspoon: You know, we had a tell on their guards and their tackles—how they like to set, if they’re going to overset on certain rushes, and if they’re going to fall for certain moves.

The game plan for the Seahawks went according to plan, too. Mike Macdonald has a saying, “Stop the run, have some fun!” It stands as the foundation of his defensive philosophy.

Seattle aims to make the offense predictable by killing the run early, forcing offenses into long-yardage or predictable passing situations. Then Macdonald uses his deep bag of pressures and front structures to attack the protections.

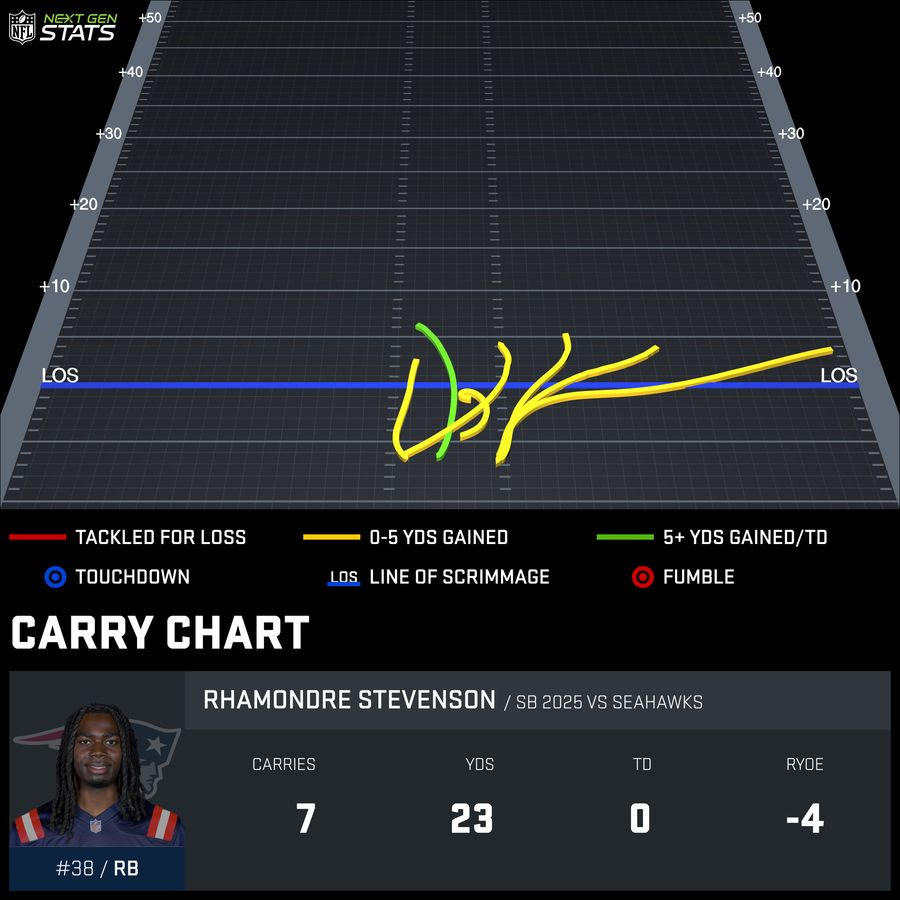

The New England offense could never take flight, though, because it could never establish the run. By halftime, the Patriots had only mustered 33 total yards on the ground on eleven carries.

Patriots running back Rhamondre Stevenson was a non-factor, going 7-for-23. Back-up RB, and someone pundits looked to have at least one explosive opportunity, TreVeyon Henderson, didn’t fare much better, finishing 6-for-19. These numbers weren't just a result of a heavy box, but a byproduct of Seattle's defensive structure, which squeezes the space from the outside in.

Even though the Seahawks play a two-high shell, their secondary tackles extremely well. Seattle runs most of its coverages from a split-field structure, but it doesn’t suffocate opponents with 9-man spacing Quarters. Instead, the Cover 2 shell “clouds” the CBs, who can become extremely active against condensed formations, which are common in the NFL.

The “secret sauce” to Seattle’s elite defense is the way the coverages sync with the front end. Though the Seahawks don’t blitz at volume, they are third in the NFL in Stunt Rate (~25%). These movements create doubt about the protection and blocking schemes for the offensive line and enhance the front four's ability to get home.

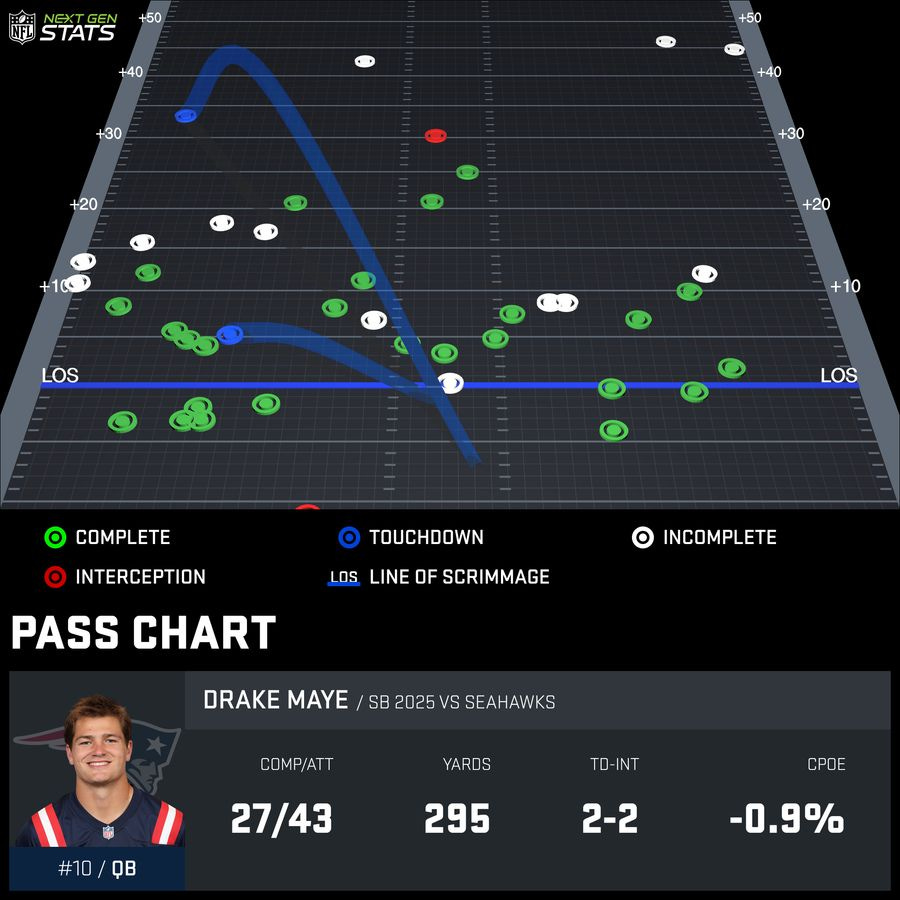

At halftime, Patriots second-year quarterback Drake Maye had gone 6-for-11 with only 48 yards through the air. He had also been sacked three times (-30 yards) and held a measly 3.2 air yards per completion. Maye was only 2-for-5 on throws over five yards. Seattle had essentially created a cinched-in grip on New England’s deep shot offense.

Though the game stood close, 9-0 at half, there was little doubt who the best team was on the field. Seattle’s offense was moving the ball; they just were not scoring touchdowns. Once Macdonald came out of the half, he knew that New England would have to pivot to throwing the ball, which would lean right into his elite secondary and the slew of coverage rotations he could use.

The highlight of the game, and what stood out as novel for a defense that rarely blitzes, was the raw attacking style of the Seahawks’ defense early in the game and on 3rd Downs. Macdonald and staff clearly saw something on film that they wanted to take advantage of.

Seattle came out of the gate swinging.

The pressure paths they used were not new and aligned with the forward modern design of the Seahawks’ defense. For modern offenses, the fulcrum of their schemes settles into the B-gap in the run game, which can be exposed in the passing game.

Macdonald’s blitz structures essentially squashed those out. Add in turnovers, and the Seahawks had the modern defensive trifecta: 1) eliminate explosives (fatals), 2) create doubt in the B-gaps, and 3) win the turnover battle.

The pressures the Seahawks used, with zone coverage behind them, were a masterclass in execution. Nothing in their game plan was “exotic.” Macdonald attacked the soft spot in the Patriots’ B-gaps and snuffed out any hope they had in winning the game.

Let’s dive into the tape!