Blitzing The Safety From A Two-High Shell

Texas A&M may have lost to Notre Dame, but they illustrated a key element to how modern defenses mesh closed-post schemes with a two-high Bracket shell.

—

Bracket is king at the college level. Ten years ago, defenses at the Power 5 level were moving away from ‘country’ (pure zone) Cover 3 coverages and diving head first into Quarters. It took until 2018 when Kirby Smart attempted to modify Georgia’s ‘match’ Cover 3 (Rip/Liz)with a ‘cheat’ Safety to combat then Oklahoma Head Coach Lincoln Riley’s RPOs and fast-paced Spread attack.

Teams then moved away from four-down (Over Front) Quarters, similar to Pitt’s Pat Narduzzi, because of the immense pressure being applied to the defense, not only in the B-gap (conflict zone) but also because the coverage essential morphed into Cover 0 if every receiver ran vertically (hello, Deep Choice!). Offenses quickly became attuned to destroying the coverage and picking apart defenses that left their conflict players in the open B-gaps.

Eventually, the Tite Front (odd spacing/no B-gaps) came into favor. Rip/Liz paired well with the front structure and basic Quarters. Even though offenses had adjusted the advancement of pre-snap motion and the still ever-present QB run game, it forced defenses to stay with their limited coverage options.

Plus, the Tite Front made it difficult to pass rush, and teams were limited to blitzing into Bear Fronts, further limiting coverage choices. Then came Vic Fangio and Branden Staley and the NFL’s two-high revolution.

In 2020, something strange happened in the NFL. The Broncos and Rams started playing most of the coverages from a two-high shell. Though teams were still playing Cover 3, it changed how quarterbacks processed the game. Before the two-high explosion, offenses could relatively accurately predict what coverage shell they would see.

At the NFL level, offenses still played from under the center, and the Wide Zone offense became en vogue. The NFL was mixing post-Spread Era principles into typical NFL run schemes like Duo, Wide Zone, and play-actions. Defenses were getting obliterated. Then, as though out of thin air, the points stopped coming.

One of the main culprits was many teams' adoption of a two-high pre-snap shell. The ability to hide coverage concepts made it more difficult for offensive coordinators to call players and quarterbacks to disicpher coverages once they turned their back to the defense on play fakes. The top-down mentality also compressed the field.

College coaches were experiencing an evolution of their own. The three-safety revolution that started in Ames to combat the Spread-heavy Big 12 was quickly permeating through the lower ranks of football. However, cornerstone coaches like Nick Saban, Kirby Smart, and Dave Aranda were not too keen on shifting their entire structures.

The Saban disciples started running most of their defense from a bracketed look, meaning the Nickle (Star) or the Slot defender to the passing strength outside the Slot WR. Offenses during the Spread-era started to move their best WRs inside to gain an advantage on slower Nickles, Linebackers, and Safeties. Bracket* solved this issue by placing a coverage-first defender on top of the offense’s most dangerous threat.

*Aranda disciples call Bracket ‘Indian’ and ‘Outlaw,’ or in Saban ‘Bracket’ and ‘Switch’

For Saban and others, adopting Rip/Liz across college football paired well with Bracket. They both had the exact pre-snap alignment from a two-high shell. Once Fangio, at the NFL level, proved you could do this from a split-field shell, many college coaches began adopting the system. Bracket is the key cog to the modern defense, and the ability to hide intentions allows the defense to expand their call menu on early downs and keeps OCs guessing at what is coming post-snap.

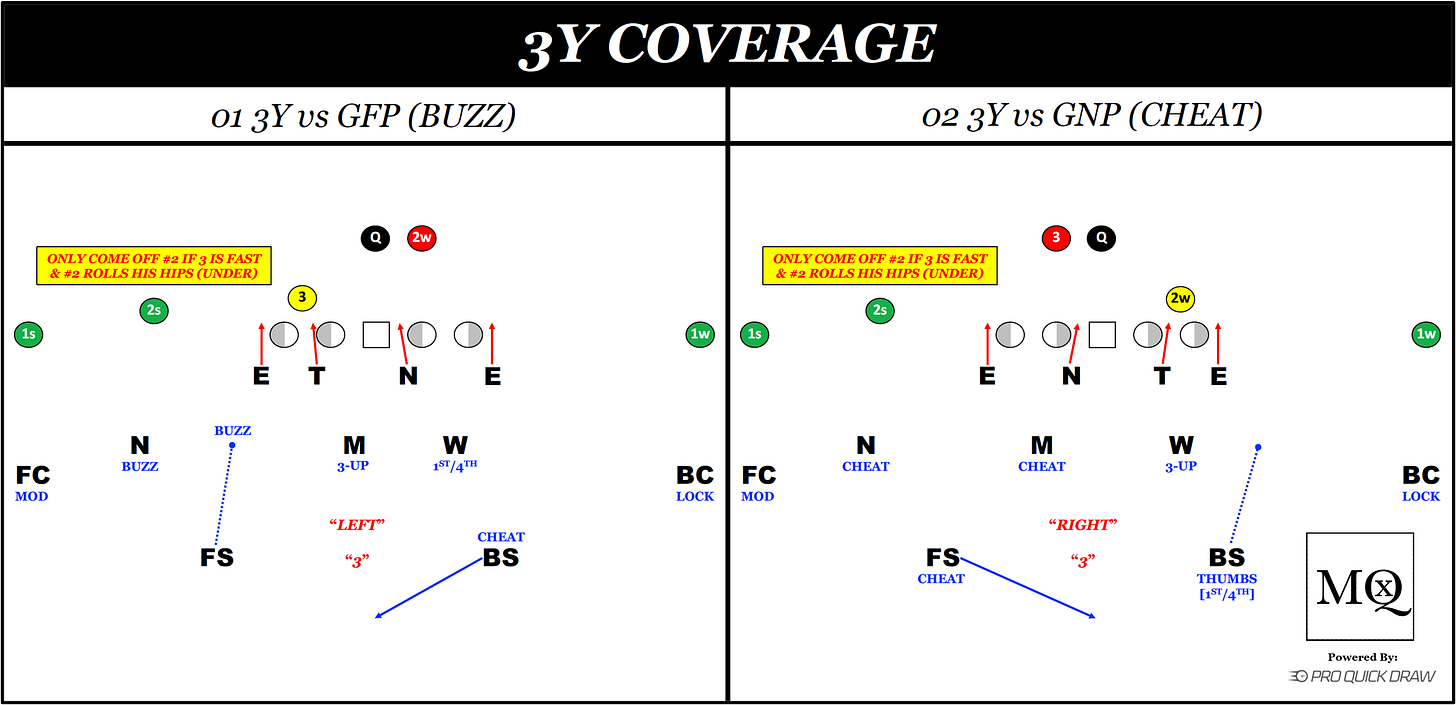

An easy way to pair Bracket on early downs is with 3-Y or a match Cover 3 that spins the Safety down to the TE’s side. Above, if the TE is to the passing strength, the Safety to the Ni will call ‘Buzz’ and spin down. If the TE is away from the passing strength (2x2), the weak Safety will sink post-snap, and the defense will play Rip/Liz.

The Ni’s responsibility, as well as that of both CBs, doesn’t change much whether running Bracket or Rip/Liz, which is why so many teams at the college level are leaning toward this pairing. Interchangable parts, or ‘same-as’ principles, are an easy way to teach complex systems to an ever-changing locker room.

Shifting to Bracket meant defenses could move back into a four-down structure. Most Bracket coaches will tell you that it is best to run from an Even Front because of the soft edge created in the C-gap playing Tite. The Safety has too far to go as the direct overhang if there is no immediate presence.

Odd-front teams still closed the B-gaps by utilizing reduction fronts that appeared to be even spacing but reduced the front (closed gaps) post-snap (odd spacing). The move to a four-down appearance also amplified the pass rush, allowing the Edges to be outside the Tackles to start the snap. In a pass-first game, a defense needs to be able to rush the passer on every down.

Once DCs understand the idea of playing an entire system from the ‘table,’ they could extend the scheme further. The natural place for that to start is the pressure package.

Creepers (replacement) and simulated pressures have become popular for teams to attack offenses on standard downs. Most see Sims as a way to attack 3rd Down with protection manipulation, but when run from an off-ball (traditional) alignment, they can be used as coordinated cut-offs in the run game.

Outside of both box ‘backers, the easiest position to incorporate within this structure was the Safeties. Teams could even bait offenses into thinking they knew what was coming by sinking Safeties early, essentially ‘showing their cards,’ only to bring them on a blitz. Teams could run them as Creepers or five-man pressures, depending on need and the ability to create issues on the line of scrimmage (LOS).

Furthermore, defenses could pair these single-high pre-snap rotations with Tampa 2 rotational coverages or non-traditional Tampas (NTTs). Though Texas A&M’s Mike Elko did not utilize Tampa drops behind his Safety pressures, the Aggies illustrated how modern defense gives the illusion of complexity to offensive opponents. Both field and boundary examples are examined.

A powerful platform used on Microsoft® Visio & PowerPoint to allow football coaches to organize, format, and export Playbooks, Scout Cards, and Presentations efficiently.